More contemporary reviews

Richard Roud, The Guardian, 22nd Mar 1968:

A couple of years ago Franklin Schaffner seemed to be one of the few new talents to come out of Hollywood. A Woman of Summer, The Best Man and last year The War Lord left us with the feeling that here was a man who might go places, once he found himself. Good as those three films were, each was so different in style and subject matter that that one could not be sure just who Mr Schaffner, so to speak, was.

Now, with Planet of the Apes I think we can come to at least a provisional conclusion. Like many Hollywood directors - but unlike the very best - he is as good as his script. In this case he's got himself quite an ingenious one about an American astronaut who propelled some 2,000 years through space/time, arrives on an unknown (or is it?) planet to find that homo sapiens and the monkeys have changed places.

The chimpanzees, the gorillas, and the orang-utans are the lords of creation; men are the slaves: mute, reduced to animal level and treated as we now treat the apes.

A promising idea, and yet ultimately too cute: it is a one-to-one allegory, and this much of the film is spent exploring this not very rewarding vein. For example, the priests refuse to believe in the evolutionary theory that apes might just possibly have developed from man, and a nice young chimpanzee social worker's idea that our hero (Charlton Heston in his usual top form) might be a "missing link" is jeered as heresy.

Except for the few (perhaps too consciously) beautiful bits of photography, the interest of the film is precisely in the working out of the plot, so I dare not reveal any more. Schaffner handles it well, but he does not add to it very conspicuously. (The screenplay, by the way, is by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling after the Pierre Boulle novel.)

It's a film to see, all right, and it does confirm Schaffner's talent. It is only that one can now see more clearly the limits of that talent, limits which are much narrower than I had hoped. This explains my sense of disappointment; on the other hand, why look a gift horse in the face, and this particular horse, if not a thoroughbred, is nevertheless something of a safe bet.

The Ape reprint shots courtesy of Jonathan Wilmot

Renata Adler, New York Times, 9th February 1968:

Planet of the Apes, which opened yesterday at the Capitol and the 72nd Street Playhouse, is an anti-war film and a science-fiction liberal tract, based on a novel by Pierre Boulle (who also wrote The Bridge on the River Kwai). It is no good at all, but fun, at moments, to watch.

A most unconvincing spaceship containing three men and one woman, who dies at once, arrives on a desolate-looking planet. One of the movie's misfortunes lies in trying to maintain suspense about which planet it is. The men debark. One of them is a relatively new movie type, a Negro based on some recent, good Sidney Poitier roles – intelligent, scholarly, no good at sports at all. Another is an all-American boy. They are not around for long. The third is Charlton Heston.

"It is no good at all." She actually said that.

He falls in with the planet's only human inhabitants, some children who have lost the power of speech. They are raided and enslaved by the apes of the title – who seem to represent militarism, fascism and police brutality. The apes live in towns with Gaudi-like architecture. They have a religion and funerals with speeches like "I never met an ape I didn't like," and "He was a good model for all of us, a gorilla to remember." Some of them have grounds to believe, heretically, that apes evolved from men. They put Heston on trial, as men did the half-apes in Vercor's novel You Shall Know Them. All this leads to some dialogue that is funny, and some that tries to be. Also some that tries to be serious.

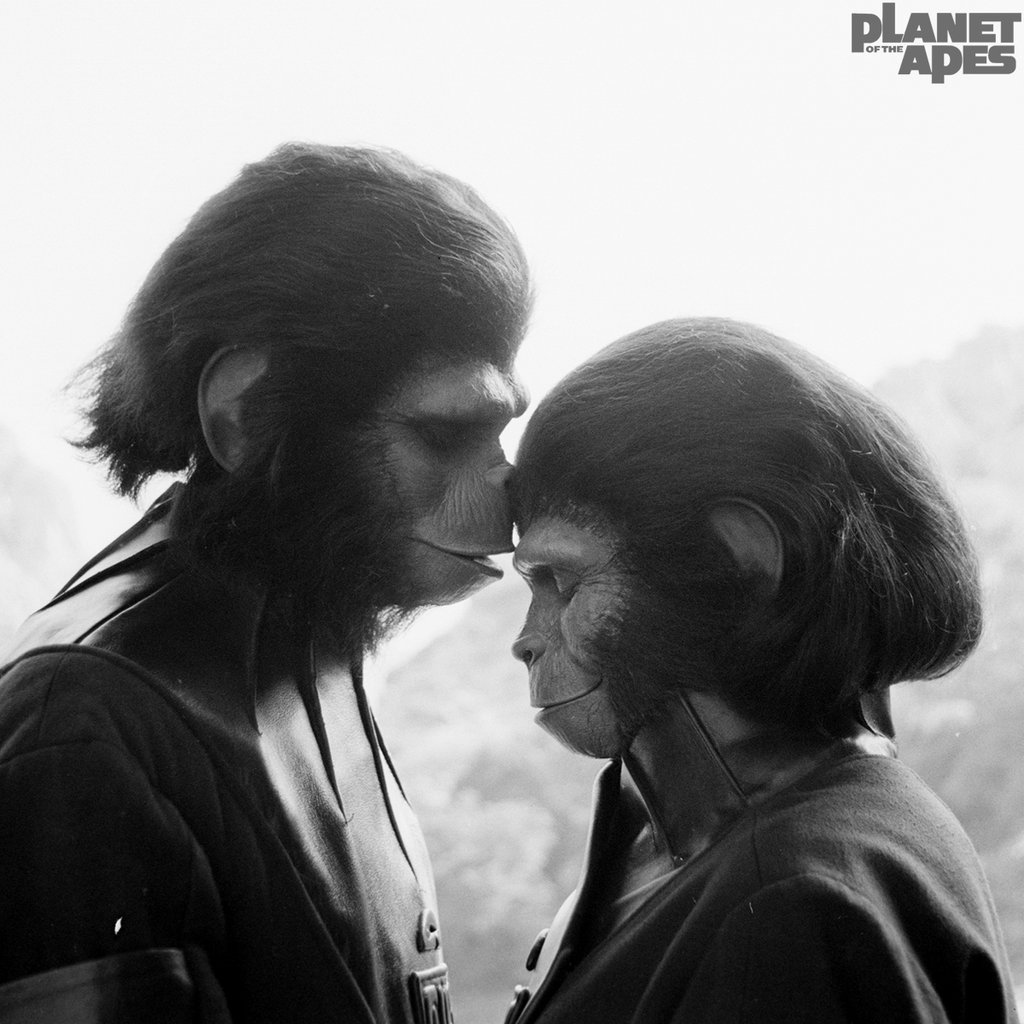

Maurice Evans, Kim Hunter, Roddy McDowall and many others are cast as apes, with wonderful anthropoid masks covering their faces. They wiggle their noses and one hardly notices any loss in normal human facial expression. Linda Harrison is cast as Heston's Neanderthal flower girl. She wiggles her hips when she wants to say something.

Pauline Kael, The New Yorker, 17th February 1968:

Planet of the Apes is a very entertaining movie, and you’d better go see it quickly, before your friends take the edge off it by telling you all about it. They will, because it has the ingenious kind of plotting that people love to talk about. If it were a great picture, it wouldn’t need this kind of protection; it’s just good enough to be worth the rush. Adapted from a novel by Pierre Boulle, Planet of the Apes most closely resembles George Pal’s 1960 version of H. G. Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine. It’s also a little like Forbidden Planet, the 1956 science-fiction adaptation of The Tempest, though it’s perhaps more cleverly sustained than either of those movies. At times, it has the primitive force of old King Kong.

It isn’t a difficult or subtle movie; you can just sit back and enjoy it. That should place the genre closely enough, without spoiling the theme or the plot. The writing, by Michael Wilson and Rod Serling, though occasionally bright, is often fancy-ironic in the old school of poetic disillusion. Even more often, it is crude. But the construction is really extraordinary. What seem to be weaknesses or holes in the idea turn out to be perfectly consistent, and sequences that work only at a simple level of parody while you’re watching them turn out to be really funny when the total structure is revealed. You’re too busy for much disbelief anyway; the timing of each action or revelation is right on the button. The audience is rushed along with the hero, who keeps going as fast as possible to avoid being castrated or lobotomized.

The picture is an enormous, many-layered black joke on the hero and the audience, and part of the joke is the use of Charlton Heston as the hero. I don’t think the movie could have been so forceful or so funny with anyone else. Physically, Heston, with his perfect, lean-hipped, powerful body, is a god-like hero; built for strength, he’s an archetype of what makes Americans win. He doesn’t play a nice guy; he’s harsh and hostile, self-centered and hot-tempered. Yet we don’t hate him, because he’s so magnetically strong; he represents American power — the physical attraction and admiration one feels toward the beauty of strength as well as the moral revulsion one feels toward the ugliness of violence. And he has the profile of an eagle. Franklin Schaffner, who directed Planet of the Apes, uses the Heston of the preposterous but enjoyable The Naked Jungle — the man who is so absurdly a movie-star myth. He is the perfect American Adam to work off some American guilt feelings or self-hatred on, and this is part of what makes this new violent fantasy so successful as comedy.

Planet of the Apes is one of the best science-fiction fantasies ever to come out of Hollywood. That doesn’t mean it’s art. It is not conceived in terms of vision or mystery or beauty. Science-fiction fantasy is a peculiar genre; it doesn’t seem to result in much literary art, either. This movie is efficient and craftsmanlike; it’s conceived and carried out for maximum popular appeal, though with a cautionary message, and with some attempts to score little points against various forms of Establishment thinking. These swifties are not Swift, and the movie’s posture of moral superiority is somewhat embarrassing. Brechtian pedagogy doesn’t work in Brecht, and it doesn’t work here, either. At best, this is a slick commercial picture, with its elements carefully engineered — pretty girl (who unfortunately doesn’t seem to have had acting training), comic relief, thrills, chases — but when expensive Hollywood engineering works, as it rarely does anymore, the results can be impressive. Schaffner has thought out the action in terms of the wide screen, and he uses space and distance dramatically. Leon Shamroy’s excellent colour photography helps to make the vast exteriors (shot in Utah and Arizona) an integral part of the meaning.

The editing, though, is somewhat distracting; several times there is a cut and then a view of what we have already seen now seen from a different angle or from much higher up. The effect is both static (we don’t seem to be getting anywhere) and overemphatic (we are conscious of being told to look at the same thing another way). The makeup (there is said to be a million dollars’ worth) and the costuming of the actors playing the apes are rather witty, and the apes have a wonderful nervous, hopping walk. The best little hopper is Kim Hunter, as an ape lady doctor; she somehow manages to give a better performance in this makeup than she has ever given on the screen before.

More Trivia

Although it is widely believed that the budget for the ape make-up was one million dollars, associate producer Mort Abrahams later revealed in an interview that the make-up was "more like half a million . . . but a million dollars made better publicity". When adjusted for inflation, the movie holds the world record for the highest make-up budget (which represented about seventeen percent of the total budget).

The spaceship the astronauts crash-land in was re-used in The Illustrated Man (1969), Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), and the short-lived TV series Planet of the Apes (1974).

Heston was first exposed to Planet of the Apes when producer Arthur P. Jacobs sent him a copy of the novel. He was not impressed with the book but nevertheless sensed that it had the potential for an interesting film.

Michael Wilson was brought in to do a rewrite of Rod Serling's screenplay. Wilson's contribution is most evident in the kangaroo courtroom scene, Wilson being an embittered target of the blacklisting Joseph McCarthy "witch-hunts" of the 1950s.

Rod Serling admitted that he spent "well over a year and thirty or forty drafts" trying to translate the novel to the screen.

The exact location and state of decay of the Statue of Liberty changed over several storyboards. One version depicted the statue buried up to its nose in the middle of a jungle while another depicted the statue in pieces.

Rock Hudson was considered for the role of Cornelius. It was eventually decided that he was too big a star and that Charlton Heston might be overshadowed.

Landon was born in 1947.

Buck Kartalian came up with the idea for his character Julius to smoke cigars.

Although he is second billed, Roddy McDowall (Cornelius) does not appear until 43 minutes into the film.

This film contains Heston's first nude scene.

Director Franklin J. Schaffner deliberately used odd, skewed angles and hand-held cameras to create a disorienting effect, much like what Heston's character experiences in this brave new world.

The opening scene set on the spacecraft was actually the very last scene to be filmed.

Jerry Goldsmith wore a gorilla mask while writing and conducting the score to "better get in touch with the movie." He also used a ram's horn in the process. The result was the first completely atonal score in a Hollywood movie.

Linda Harrison, who plays Nova, was having an affair with producer Richard D. Zanuck at the time of production. In the year of the film's release, Zanuck divorced his first wife and married Harrison. The couple were married for nine years and had two children. She was actually pregnant and starting to show towards the end of the shoot, which required careful posing on her part to conceal it.

Not only did Roddy McDowall and Kim Hunter spend time at local zoos studying the behaviour and mannerisms of apes, they practiced speaking through the ape make-up in front of the mirror. Eventually, they taught the rest of the cast the best way to articulate the facial appliances.

The scarecrows that the astronauts discover were supposed to be noted as being their first sign of intelligent life. Similarly, a deleted line later in the film talks about how they delineated the borders of the Forbidden Zone.

When Taylor (Charlton Heston) says, “To hell with the scarecrows,” the studio wanted to cut the word “hell” to make the scene more family friendly.

There are no female gorillas or orang-utans in the film.

Charlton Heston and Linda Harrison are the only actors to appear in both this film and Tim Burton’s “re-imagining”.

The make-up on the apes was so complex that they were only supposed to eat soft foods and milkshakes. The actors who smoked were provided with cigarette holders to avoid cigarette contact with the appliances. Chambers had to often redo actors’ make-up when they ate solid food against his advice. The apes were also instructed not to eat in the commissary, and Hunter and McDowall often had to eat in front of a mirror so as to not disturb their make-up.

The iconic line, “Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!” was originally written as “Stand back, you bloody ape!”

An oppressed race of baboons were originally written into the script, but they were removed, possibly due to make-up difficulties and the fact that baboons are actually a species of monkey.

The famous “See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil” shot was originally put in as a joke and not intended for the final film. However, when it was included in a test screening, the audience had such a positive reaction to it, the filmmakers left it in the final cut.

The spacecraft onscreen is never actually named in the film. But for the 40th anniversary release of the Blu-ray edition of the film, in the short film created for the release called A Public Service Announcement from ANSA, the ship is called "Liberty 1". She was launched from Cape Kennedy in Florida on January 15, 1972.

No comments:

Post a Comment